In recent decades, Scotland has increasingly influenced the world of style and haute-couture. However, its contribution to fashion goes far beyond the catwalk. Its influence on style and cultural identity can be seen in the subcultures of Grunge, Goth and Punk. Tartan became the identifiable pattern of the Punk subculture, which spread around the globe to become one of the most recognisable countercultures in history, linking the Scottish fabric with the anti-establishment feelings of the time.

When you consider the history of tartan, it is little wonder that it became the style staple of these nonconformist crusades. The wearing of tartan was banned and became a punishable offence in Scotland for 76 years after the Battle of Culloden, until it was later repealed by an Act of Parliament in 1782. It wasn’t until 1822, when Sir Walter Scott pulled off an incredible PR stunt during the visit of King George IV to Scotland, that tartan became a recognisable part of Scottish culture again. It was around this time that tartan became attributed to clans.

The Murray of Tullibardine tartan can trace its origins to the 1745 Jacobite rising. The muted red-based tartan with shades of grey and green is still worn by the Mansfield family today and can be seen in the soft furnishings of the palace. It also forms a key part of the uniform worn by the employees who work at Scone. The earliest physical evidence of the tartan is a piece in the pattern book, Wilson’s of Bannockburn, dated 1830. However, we know from a collection of five 18th century portraits that it was in existence before this date. The painting ‘Portrait of a Jacobite Lady’ by Cosmo Alexander c1740-46 depicts a young woman holding a white rose, a symbol of the Jacobite cause. Although the identity of the sitter remains much debated, the tartan has been painted with such intricacy and clarity, that it is almost certainly the Murray of Tullibardine design. The family tartan appears again in the iconic portrait of Flora MacDonald painted by Sir Allan Ramsay in 1749. The young woman, who famously helped Bonnie Prince Charlie escape from Scotland after the Jacobite defeat in the Battle of Culloden, wears a length of tartan draped across her shoulders. The tartan is clearly that of the Murray of Tullibardine.

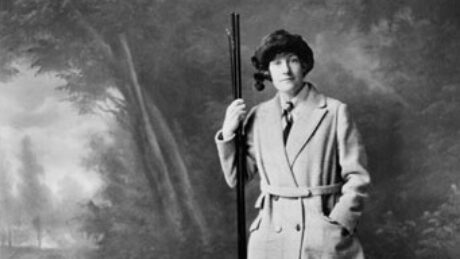

Scotland’s textile industry has always been associated with quality. No autumn or winter collection would be complete without tweed, which remains one of Scotland’s most prodigious exports. Handwoven by islanders in their homes on the Outer Hebrides for centuries, tweed was originally known as ‘clòr-mòr’ which meant ‘big cloth’ in Scottish Gaelic. The heavy weave cloth provided ideal protection against the bitter Scottish winters. It was also used as a form of currency among the islanders who would barter with lengths of the cloth. The unique way in which the tweed is made has been protected by the Harris Tweed Act since 1993, which has worked consistently to promote and protect this ancient crofting industry. How it became synonymous with country and sporting attire though is due entirely to the vision of Lady Catherine Herbert, wife of the 6th Earl of Dunmore. She inherited the Outer Hebridean estates on the death of her husband and immediately noticed the potential of the hard-wearing fabric. She commissioned lengths of the cloth to be made into jackets for the ghillies and gamekeepers who worked on her estate.

There are two Mansfield tweeds. However, unlike the tartan, the two distinctive family tweeds can trace their provenance. The Glenurquhart check was designed by both Dorothea Carnegie, the present Earl’s grandmother, and the wife of her first cousin, HH Princess Maud, Countess of Southesk in 1965 and is still used on the estate today. The other version, which was designed solely by the Dorothea Carnegie in 1949, is woven from the wool of Scone Palace’s flock of pedigree sheep and continues to be worn by the family. Both tweeds are a familiar sight around Scone Park.

Through the generations, the Murray family have made notable contributions to inspiring and promoting fashions and styles. In fact, one of the most unforgettable trends in British history can be directly attributed to an ancestor of the present Earl of Mansfield. In April 1774, David Murray, the 7th Viscount Stormont returned briefly to England from his role as Ambassador in Paris, and famously gave a 4ft long ostrich feather to Georgiana, the Duchess of Devonshire. The Duchess, who was the wife of William Cavendish, the 5th Duke of Devonshire, was known for her beauty and charisma, and was one of the fashion icons of her time. Like A-list celebrities and influencers today, every outfit or accessory she wore was immediately adopted by the public. She is especially remembered for her extraordinary hairstyles, which quite literally, reached new heights. On receiving the long ostrich feather from the 7th Viscount Stormont, Georgiana took it upon herself to have the single length of plumage incorporated into her hair. It was attached in a wide arch across the front of her elevated wig. It became the must-have accessory overnight. However, the trend was to be short-lived. Queen Charlotte, wife of King George III, saw the accessory as too excessive and too expensive for most of the ‘ton’ and banned the use of ostrich feathers as hair accessories at court. And yet, despite its fleeting use, it remains emblematic of the iconic style she promoted.

Making a statement through the concept of fashion continued in later generations of the family. In 1903, Tzar Nicolas II of Russia held a lavish ball in the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg. It was to be the last ball ever hosted by the Imperial family. The guests, most of whom were from the highest echelons of Russian society, were asked to attend in 17th century style costumes of aristocratic boyars. The guests arrived in exquisitely extravagant garments with layers of jewels over sumptuously embroidered fabrics.

During this time, The Hon Lancelot Carnegie, great-grandfather to the present Earl of Mansfield, was a diplomat stationed in Saint Petersburg. He and his wife, Marion Carnegie were invited to attend. There was much excitement in the run-up to the ball, with all of the princesses, archduchesses and their husbands vying for the most opulent costumes to be made. The Carnegies could not possibly compete financially, so Marion had to think creatively. She contacted a cousin in London who was coming out for the ball, and asked him to bring a box containing an important part of her costume. Shortly after, a 6ft long box was entrusted to him, which he nobly delivered to Saint Petersburg.

The night of the ball arrived. As the rooms of the Winter Palace dazzled with the reflections of shimmering jewels, and the air filled with the voices of Russia’s social elite, a hush suddenly swept through the opulent crowd as Marion, who had deliberately arrived late, entered the room. She was considered to be one of the great beauties of her generation, with long red-gold hair and a tall, sinuous figure. In complete contrast to the bejewelled, amorphous costumes worn by the Russian guests, Marion entered wearing a long, plain white dress, with her hair gently cascading down her shoulders and back. This in itself had raised a few eyebrows as it was regarded as immodest for a married woman to wear her hair loose. White flowers had been interwoven into her curls and she held a single white lily. But the most magnificent part of her costume was the contents of the wooden box brought to her from London. From her shoulders sprouted two huge, pure white, feathered swan’s wings. Her appearance caused a sensation, casting a shadow over all of the other costumes. Not a single jewel decorated her ensemble, allowing the imagery of her simple garment to create the impact by itself.

Creating elegance through simplicity in style is synonymous with one of the most celebrated designers in history; Christian Dior. In September 1960, The Dowager Countess of Mansfield hosted a catwalk show in the palace in collaboration with the distinguished fashion house. The charitable event, which was in aid of The Queen’s Institute of District Nursing and The Perth and Kinross Union of Boys’ Clubs, was an extravagant affair. The family had only recently moved back into the palace and so there was much curiosity surrounding the show. Lady Malvina, the present Earl’s aunt, along with other members of the family worked hard to bring the event about. The Dior clothes were left on rails overnight in a room which had been designated for the models to change in. Family anecdotes tell stories of how they had fun trying the outfits on before the event. Guests were enraptured as the models paraded through the state rooms, bringing the ultra-feminine silhouettes of the designs to life. Every room was filled with guests who had travelled for miles to attend. The event raised a significant amount of money for the aforementioned charities, whilst bringing one of the highest names in haute-couture to a little corner of Perthshire.

As we approach London Fashion Week in June, it is all too easy to think only of the big names whose designs grace the catwalks. Scottish designers like Christopher Kane, Samantha McCoach and Judy R Clark are blazing a trail in the fashion world, turning to their cultural heritages for inspiration. But the question of whether fashion ever truly evolves or whether it is merely a reimagining of what has been before will always be a conundrum. Yet whether it begins with a simple 4ft long ostrich feather or a pair of angelic-like swan wings, we all have the potential to make our own marks and leave a style legacy when we reach the end of the catwalk.

Other News

Garden Lovers Invited to Vote in UK First at Scone Palace Garden Fair

14th May 2025

Top Five Must Do Activities at Scone Palace Garden Fair

13th May 2025

Dobbies Garden Centres Joins the Scone Palace Garden Fair

12th May 2025

The Crowning Place of Scottish Kings

04th May 2023

The Palace Awaits

29th March 2023

Snowdrop Festival

26th January 2023

Georgina Ballantine’s Giant Catch

14th October 2022

Man's Best Friend

01st September 2022

British Cut Flowers Week & The Garden Fair

05th July 2022

The Celebration of Easter

19th April 2022