On arrival at the palace, many visitors ask how Scone became the Crowning Place of Scottish kings. There are many reasons as to why Scone became the inauguration site of Scottish monarchs, or Kings of Scots, but to understand it fully, we need to go back to the 7th century.

At this time, Scone was an important religious site. At the beginning of the 8th century, a group of early Christians called the Culdees settled at Scone. They were a monastic community, believed to have originated in Ireland as followers of St Columba. During the 600 years they were present in Scotland they established 13 monasteries, 8 of which were affiliated to cathedrals. Very little is known about them, but by choosing to settle at Scone, they ensured its future as a place of religious significance, and therefore, a place befitting the crowning of kings.

By the 12th century, Scone had confirmed its status as a site of Christian importance. In 1114, Alexander I founded an Augustinian priory at Scone beside Moot Hill. Fifty years later, Malcolm IV, who himself was crowned at Scone in 1153, elevated the priory to the status of abbey.

But Scone had an ancient pagan importance as well as a religious one; it was the home of the Stone of Destiny. The Stone of Destiny, or the Stone of Scone is surrounded in controversy. Today it resides in the Crown Room at Edinburgh Castle, but will be moved permanently to the city of Perth, which lies on the other side of the River Tay to Scone, in 2024. The ancient coronation stone has played an integral part in the enthronements of Scottish monarchs for centuries. But where did the stone come from and how did it come to be at Scone?

The origins of the Stone of Scone are shrouded in mystery. Some believe it is Jacob’s Pillow; the stone upon which Jacob was sleeping when he had a vision of angels. It is thought that the stone made its way from the Holy Land to Ireland. Another theory is that Fergus Mór mac Eirc, possible King of Dál Riata (a Gaelic kingdom encompassing the western seaboard of Scotland) brought the stone from Ireland to Argyll. But there is one theory that seems to be the most universally accepted; that it was Kenneth MacAlpin, later Kenneth I, who brought the stone to Scone.

Kenneth MacAlpin was born on Iona in 810. By 843, he had defeated some Picts, allied and merged with others, battled the Britons and clashed with the Vikings. Kenneth I conquered and annexed the ancient provinces to create the kingdom of Alba, and as a result, is considered to be the father of Scotland as the first “King of Scots”. Once he had Pictland under his control, he moved sacred relics from an abandoned abbey on Iona to nearby Dunkeld, whilst the coronation stone came to the capital of his new kingdom, Scone. He was the first king to be crowned on the stone at Scone in 843.

During the following 450 years, forty-two kings would be crowned at Scone. The earlier ceremonies would have been pagan and performed with minimal religious references. They were a confirmation of power and an assertion of lineage. There are very few surviving records of the early inaugurations at Scone. Although we can draw comparisons with other sources and king-making traditions, we have to imagine them. We can picture Macbeth ascending Moot Hill in August 1040. Perhaps there were flags viscously flapping in the high winds of late summer? Perhaps the daylight was tinted with the purple hue of hillside heather in full flush? Did he stand tall; dominating the ancient pagan gathering place as he surveyed the kingdom at his feet? Did he address the medieval throng? What was his countenance when he and his gathered Guardians made their vows to the Scottish people by emptying the soil carried in their boots to contribute to the hillock that represented all of Scotland, earning its name as ‘Boot Hill’ in folklore? We may never know the answer to these questions and will instead continue to be guided by the imaginations of Hollywood directors.

The point at which the crownings became more religious is uncertain. It would seem logical to assume that the shift occurred in accordance with the founding of Scone Priory in 1114 and the subsequent promotion to Scone Abbey in 1164. The first known pictorial and written sources detailing the elements of a ceremony date from 1249 and describe the inauguration of Alexander III, who was hurriedly enthroned at Scone aged seven (to head off any other claimants making a go of it). Although written 200 years later by Walter Bowers, Canon of Inchcolm, his account does provide some detail into the sequence of events and gives us concrete evidence of the coronation stone being used. He describes the inauguration of Alexander III as having been comprised of two distinct parts, separated with a procession by which the ceremony moves from the abbey out onto Moot Hill. This would suggest that Alexander’s enthronement had an initial Christian ecclesiastical element within Scone Abbey, followed by a ceremony on Moot Hill, on which the Stone of Scone would have been placed. The second part of the ceremony, possibly harking back to a more ancient Pictish and pagan ritual, predates the Culdees. Indeed, it was recorded that the boy-king was less than enthusiastic about this part of the ceremony. In the end, after some initial reluctance, he was forced to ascend the hill to be acclaimed by the people.

The last ceremony in which the coronation stone would be used at Scone was the crowning of John Balliol in 1292. After the death of Margaret of Norway, granddaughter of Alexander III, Scotland entered a destabilising interregnum. King Edward I of England was invited by the Scottish regents or “Guardians of Scotland” to help them solve the impending succession crisis and avoid civil war. Edward accepted but seeing an opportunity to subjugate Scotland and become Lord Paramount, he insisted upon gathering the group of 13 claimants to the Scottish crown in northern England where he happened to have a very large army in camp - rather useful leverage! Settling eventually on John Balliol, who was a great-great-great grandson of David I through his mother, and easily manipulated by Edward who was king in all but name. In 1295, a group of prominent Scottish noblemen, greatly concerned by Balliol’s ineffectiveness, appointed a Council of Twelve at Stirling. To safeguard the vulnerable Scotland, the Council signed a treaty with France. In 1296, Edward I launched an attack on Scotland, during which he confiscated the Stone of Scone, taking it to Westminster where it would remain for the next 700 years. As for John Balliol, he was deposed shortly after, just four years after his inauguration on the stone at Scone.

The stone was now in England, Scotland was in the grip of the First War of Scottish Independence, and more worryingly, the country was without a monarch. Enter Robert I, more popularly known as Robert the Bruce. Of all the ascensions to the Scottish throne, Robert I’s is undoubtedly the most dramatic. In 1306, Robert seized the throne with the blood of John Comyn barely dry on his hands. Comyn was a rival for the kingship through his father, who was a descendent of Donald III. On February 10, Robert met with Comyn at the church of Greyfriars in Dumfries. The meeting quickly became heated, culminating with Robert stabbing Comyn before the altar; an act for which he was excommunicated by the Pope, a punishment that would haunt him for the rest of his life. He quickly fled, arriving at Scone 43 days later. But whilst his coronations are marred in controversy, he ensured that subsequent coronations would be given the status they deserved, for it was Robert I who finally secured the rite of unction for Kings of Scots in 1329 (having been welcomed back into the church). From here on, coronations at Scone would involve the anointing of papal oil as part of the ceremony. Scotland was finally entitled to have a king who was recognised by God and thus equal in status to other monarchs across Europe. And so, David II, son of Robert the Bruce, was the first Scottish monarch to be anointed at Scone in 1331.

At this point, the crowning ceremonies at Scone moved further away from non-religious rituals towards Christian deference. A coronation roll was created in 1331 in preparation for David II’s coronation. Although there is no record of the roll, it is understood to incorporate certain religious ceremonial practices, which would have been administered by a bishop. We also know that the coronation of Robert II in 1371 occurred over two days, with the Bishop of St Andrews crowning the king in Scone Abbey on the first day before paying homages and swearing allegiances on Moot Hill on the second. The last Scottish king to be crowned at Scone was James IV in 1488. As with Robert II, his coronation was ordained by the church with Robert Blackadder, Bishop of Glasgow, placing the crown upon his head in Scone Abbey.

In 1559, during the Scottish Reformation, a mob of Protestants, who had been riled by the preachings of John Knox, descended on the abbey from Dundee and burned it to the ground. Scone Abbey, the once home of Scottish kings, was gone. Only the Abbot’s Palace and Moot Hill remained. But Moot Hill was to rise in prominence once more. In 1651, whilst England was in the iron grip of Oliver Cromwell, the Parliament of Scotland proclaimed Charles II King of Scotland, France, Ireland and England. He was the last king to be crowned at Scone.

Throughout history, crownings at Scone have been either pagan, Christian or a combination of both. In the years before Scone Abbey was founded, the Stone of Scone played an integral part. It was the symbol of Scottish sovereignty. Whoever sat upon it, had legitimately claimed the right to be King of Scots. This month will see the Stone of Scone make its way down to Westminster for the coronation of King Charles III. It will be carefully placed within the Coronation Chair, designed by Edward I of England to house the stone in 1301. After the coronation, the Stone of Scone will be returned to Scotland and Edinburgh Castle, where it will stay until the new Perth Museum is ready to receive it, scheduled to be during 2024. Once installed in the new Perth Museum, you will be able to visit both the Stone of Scone and Scone Palace, the crowning place of Scottish Kings, all in one day.

If you would like to learn more about the coronation of Charles II, please head to the blog titled

‘The Last Coronation’.

Other News

Garden Lovers Invited to Vote in UK First at Scone Palace Garden Fair

14th May 2025

Top Five Must Do Activities at Scone Palace Garden Fair

13th May 2025

Dobbies Garden Centres Joins the Scone Palace Garden Fair

12th May 2025

The Palace Awaits

29th March 2023

Snowdrop Festival

26th January 2023

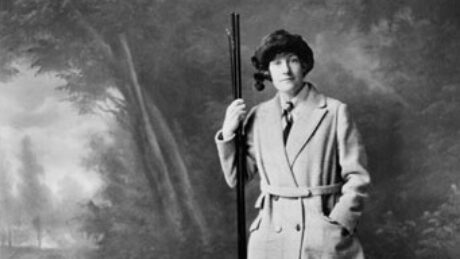

Georgina Ballantine’s Giant Catch

14th October 2022

Man's Best Friend

01st September 2022

British Cut Flowers Week & The Garden Fair

05th July 2022

Scotland, Scone and Fashion

01st June 2022

The Celebration of Easter

19th April 2022