The English naturalist, Charles Darwin, once said, ‘A man who dares to waste one hour of time has not discovered the value of life’.

The English naturalist, Charles Darwin, once said, ‘A man who dares to waste one hour of time has not discovered the value of life’. As human beings, we seem to be endlessly fascinated by time. Whether it’s to plan, calculate, or even control it, we’re continually trying to make it work for us. We are precious about it. We don’t want to waste a moment. And yet, even when we have it in our grasps, no matter how fleetingly, we rarely appreciate its full value. But, there is something about the long Easter weekend that makes us sit up and pay attention. The four long days stretch out before us, and whether we choose to use them productively or luxuriate in them, we make plans, determined that we will not waste them. Of course, invariably, our hopes are thwarted, as the realities of motorway tailbacks, torrential rain, home improvement disasters and long queues at airports remind us that when it comes to time, there are no refunds. Once you’ve cashed in your chips, you have to spend your winnings wisely.

The timing of Easter is ideal. As the increasing hours of daylight draw us out from domestic repose, we experience a sense of revival and renewal as the world materialises and comes into being once more. But throughout history, the exact point in the year on which Easter should fall, has been intensely debated and argued.

Easter is a moveable feast in the Christian calendar. This means, unlike Christmas and other dates in the liturgical calendar, it can move around from year to year. Understanding as to why this is the case is based on multiple factors. Firstly, Easter has to fall on the first Sunday after the paschal full moon, that is the first full moon on or after the 21st of March. Secondly, the phase of the moon (lunar month) and the season (solar year) must coincide. Thirdly, Easter must fall on a Sunday in both the Gregorian and Julian calendar. And lastly, Easter must be in accordance with Jewish Passover; the date that Christians recognise as being the one on which Jesus was crucified.

The mathematical and scientific process of calculating calendar dates is known as comptus. Whilst most dates are universally agreed upon based on evidence or limited factors, Easter, as you have seen above, is determined by so many considerations, that it renders it fluid and open for interpretation. Today in Scotland, we celebrate Easter in accordance with the Gregorian calendar. For those readers who are unsure, the Gregorian calendar was introduced in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII, who recalculated the length of the year, shortening it by less than a day, thus bringing it in line with the solar year. But how we came to observe Easter on the day we do is due to a small historical event that so few people know about. And it happened right here, on Moot Hill in 710 AD.

Between the early years of the 7th century and the Reformation in 1559, events at Scone helped to shape the religious landscape of Scotland. The first people to settle at Scone were the Culdees, a monastic community and followers of St Columba. The Culdees were known as ‘servants of God’. Although very little is known of their lives and practises, it was understood that, whilst they lived in a monastic manner, they never actually took vows and were not overseen by a bishop. They sought a life of piety, believing in the ‘perfection of sanctity’. During the Middle Ages, the Culdees founded 13 monastic communities across Scotland, 8 of which were affiliated with a cathedral. It is not hard to imagine them at Scone, tending to their vegetable gardens and practising choral worship.

Scone continued to attain recognition as an important religious centre well in to the latter half of the Middle Ages. In 1114, King Alexander I founded an Augustinian priory adjacent to the ancient site of Moot Hill. The Priory was later elevated to the status of Abbey during the reign of King Malcolm IV in 1169. It’s no wonder then that such a religiously significant setting should become the crowning place of Kings of Scots. The Abbey stood in the grounds of Scone until 1559, when it was burned down by a riotous mob from Dundee during the Scottish Reformation. This was a time of widespread religious conflict as worshippers sought to break from the papacy of Rome and establish a Scottish church based on Calvinist ideals. Deciding which ecclesiastical path to follow has been the basis of most storylines in Scotland’s religious journey. And so, we return once more to Moot Hill in 710 AD.

At this time, Scone was the capital of the Pictish kingdom, Pictland. King Nechtan was King of the Picts between 706 and 724. Often referred to as the ‘Philosopher King’ he was responsible for some of the most significant reforms in Pictland, and it is he who set the date for Easter which we still observe to this day. Little documental evidence remains from this time, but there is one short written account, the only surviving narrative source of the time, which gives us a brief insight into the events of that day.

‘The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba’ written in 906 records the period of Scottish history between the reign of Kenneth MacAlpin (843 - 858) and the reign of Kenneth II (971 - 995). It describes the careers of the kings and provides an insight into the emerging Kingdom of Scotland through their individual perspectives. The chronicle tells us that in the 6th year of his reign, King Nechtan met Bishop Cellach - who is thought to have been the first Bishop of Scots - on Moot Hill. There they decreed that Easter should be observed in accordance with the Roman Church, rather than the Celtic one, thus transferring his kingdom to the Roman calendar. Now this may not seem overly significant at first, but when you consider the wider repercussions of this decision, it suddenly becomes far more consequential. The dating of Easter had continually perturbed and exasperated the churches of Britain and Ireland. The famous Synod of Whitby in 664, where the Catholic Bishop Wilfrid and the Celtic Abbess Hilda, along with other representatives of their churches, met in Northumbria to decide whether to follow the Celtic or Roman calendar. This demonstrates how seriously this matter was being taken and the struggles it presented. King Nechtan, however, was not so malleable. He created his own denouement, spurning the church of St Columba, dismissing the observances of the Celtic calendar and aligning his kingdom with the Roman system of dating.

But for those readers who feel he was reckless, throwing Scotland’s religious identity carelessly into the ecclesiastical winds on a whim, may take some comfort in the knowledge that it was not a decision he made entirely without counsel or guidance. According to The Venerable Bede, an English monk from the Monkwearmouth-Jarrow monastery in modern day Tyne and Wear, King Nechtan sought advice from Abbot Ceolfrid before arranging the meeting on Moot Hill. In Bede’s scholarly account titled Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written around 731, he describes how King Nechtan, endeavouring to seek guidance on the dating of moveable feasts and observances, wrote to Abbot Ceolfrid. As Ceolfrid was the warden of Bede - a man who had devoted much of his life to studying the intricacies of comptus - he was fully conversant in the science of calculating dates. It was after this correspondence that King Nechtan orchestrated the meeting on Moot Hill; a meeting that would decide the date of Easter in Scotland today.

Other News

Garden Lovers Invited to Vote in UK First at Scone Palace Garden Fair

14th May 2025

Top Five Must Do Activities at Scone Palace Garden Fair

13th May 2025

Dobbies Garden Centres Joins the Scone Palace Garden Fair

12th May 2025

The Crowning Place of Scottish Kings

04th May 2023

The Palace Awaits

29th March 2023

Snowdrop Festival

26th January 2023

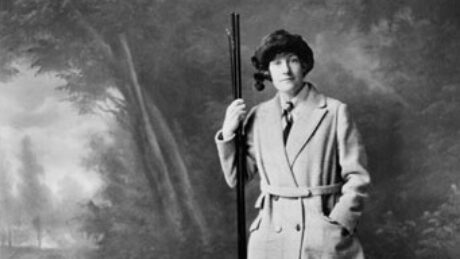

Georgina Ballantine’s Giant Catch

14th October 2022

Man's Best Friend

01st September 2022

British Cut Flowers Week & The Garden Fair

05th July 2022

Scotland, Scone and Fashion

01st June 2022